blogposts

The future of Agentic Software Development

By Patrick Chugh (December 2025)

TL;DR: Documentation always drifts from reality because code evolves but specs don’t. Spec-Driven Development (SDD) using LLMs flips this by making specifications generate code rather than merely guide it. Using Generative AI, structured specs become the source of truth that automatically produces implementations. The workflow has four phases that turn clear rules and instructions in English into code. The result: documentation that can’t lie because the code derives from it. SDD won’t replace developer judgment or fix bad architecture, but it shifts craft from writing code to precisely defining intent.

The Source of Truth Problem

For decades, we’ve treated code as the source of truth. And in a sense, it is. Code is reality. Whatever is deployed is what users experience for better or worse, regardless of what any document says.

But code has a critical limitation: it tells you what the system does, not why. The intent gets lost. Six months later, you’re staring at a function wondering whether it’s a bug or a feature, whether that edge case handling was deliberate or accidental, whether you can safely refactor or if some downstream system depends on that exact behaviour.

So, we end up in an uncomfortable middle ground. Specs describe intent but drift from reality. Code is reality but obscures intent. Neither serves as a reliable source of truth for the whole picture.

Spec-Driven Development (SDD) proposes a way out: what if specifications generated code instead of merely guiding it?

What about your docs? They’re a lie!

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: by the time you finish reading your project’s documentation, it’s probably wrong.

Not because anyone wrote it badly. Not because the original authors were careless. It’s wrong because software development has a fundamental problem: code evolves, but specs don’t.

With the pace of change accelerating in the world, it’s out of date often shortly after it’s written. That requirements document you spent days writing? It’s now historical fiction; a snapshot of what you intended to build, not what’s actually running.

Don’t think so? Think about the last time you updated a PRD after the hotfix at 2am or after the “temporary” workaround that’s now load-bearing. What about after your company’s product pivoted based on user feedback? We’ve all been there. If your documentation has stayed perfectly current through all of that, I’d love to know your secret.

This is the essence of the drift problem, and it’s been haunting software development since the beginning.

Flipping the Relationship

The core idea of SDD is a total SDLC inversion. Instead of specifications serving code, code serves specifications. The PRD isn’t a guide for implementation. It’s the new source of truth that automatically produces implementations in code and infrastructure via IAC scripts. Technical plans aren’t documents that inform coding. They’re precise definitions that evaluate options, record decisions on why a particular approach or framework was used, that subsequently generate your tech stack.

This isn’t just philosophical. It’s now technically feasible because Generative AI has reached a point where well-structured specifications can reliably produce working implementations. Visit GitHub’s Spec Kit for a ready to use framework you can use today if you want to experiment with this approach.

Of course we’re not talking about perfect implementations, we’re not there yet, but solid outputs that match intent far better than ad-hoc prompting or ‘Vibe Coding’ ever could. They may not be perfect now but just imagine what they can do once the LLMs catch up to this new way of working.

The key insight is that document structure matters. Vague prompts produce chaos. Lack of organisational knowledge, incorrect data and faulty assumptions mean your app will never make it to production. Garbage in, Garbage out. But if you could enforce discipline to ensure specifications are precise, complete, are research based and follow strict templates? Now those produce systems you can actually maintain.

When this works, the drift problem disappears. Specs can’t fall out of sync with code because the code is derived from the specs. Update a requirement, regenerate the affected components. Job done. Want to see how that Python app you wrote would perform if re-written in Golang? Just update the technical plan and rinse and repeat. Now the documentation is the system.

What Changes Day-to-Day

When you commit to specifications as your source of truth, the workflow shifts in interesting ways.

Debugging moves upstream. Found a bug? Before diving into the code, ask: is the spec wrong, or did generation go sideways? Often, it’s the former. Fix the spec, regenerate, move on. You end up fixing root causes instead of patching symptoms.

Pivots become systematic. Product team wants to change direction? Update the requirements, let the ripple effects flow through the technical plan, regenerate what’s affected. What used to be a multi-sprint fire drill becomes a methodical transformation.

Documentation stays honest. In traditional development, docs are born accurate and decay through neglect. In SDD, your specs are the system definition. They can’t drift because the code comes from them, not the other way around.

Post-deployment metrics feed back into the specifications. This is the one that gets me. Errors in your log file, user telemetry and instrumentation data, CPU/RAM metrics lead to fixes and improvements that work their way back into an updated specification. This closes the loop.

Why This Is Happening Now

Two forces converged to make this practical.

First, Generative AI crossed a capability threshold. Language models can now understand complex requirements and produce coherent implementations. They’re not just glorified autocomplete tools. They can reason about system design, identify edge cases, and translate business logic into working code.

Second, modern software is brutally complex. A capable developer twenty years ago could hold an entire system in their head. Today’s applications integrate dozens of services, each with their own authentication, rate limits, and failure modes, often all written by different teams. Add to that the high turnover in the enterprise software market and changing roles of staff. You quickly realise keeping all of that aligned with original intent through human memory or tribal knowledge alone is a losing battle.

The Practical Shape of SDD

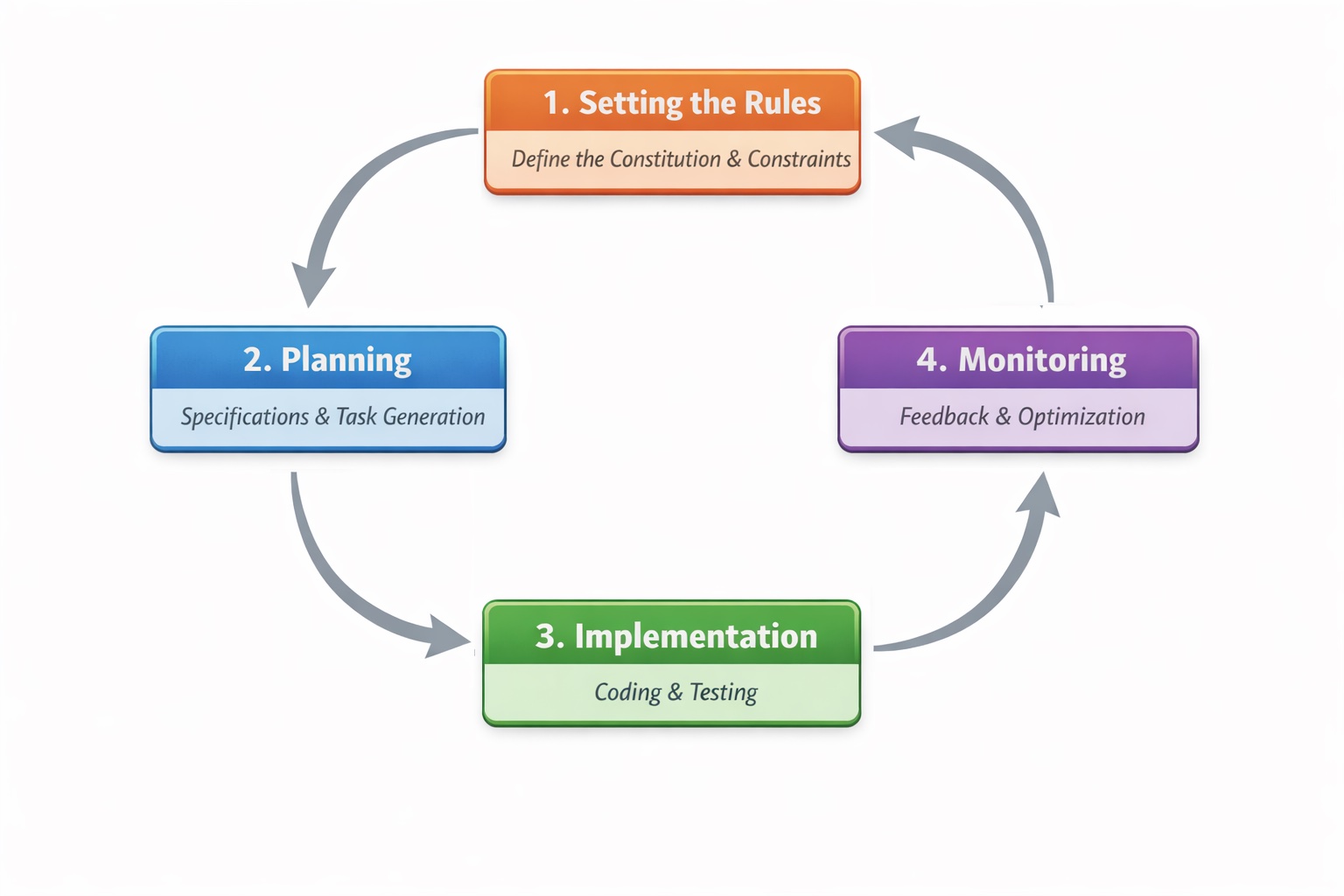

If you’re wondering what this looks like in practice, it’s built around four phases.

Phase 1: Setting the rules. You start with what SDD calls a “constitution”, a set of non-negotiable principles for your project. Think of it as your team’s immutable architectural commandments engraved on a stone tablet. For example: Every library must be modular. Every feature gets tested before implementation. No over-engineered abstractions without documented justification. The AI model will also research existing organisational policies, coding standards, approved libraries and security controls to ensure the constitution is comprehensive. These constraints sound limiting, but they prevent the kind of wayward coding that current LLMs are notorious for.

Phase 2: Planning. From there, the new intended work and high-level requirements are decided upon which flows through specification, planning, and task generation. AI will create a specification that transforms a rough idea into a structured document with user stories, acceptance criteria, and explicit markers for anything needing clarification. Humans fill in the gaps and clarify any ambiguities. Planning translates that spec into technical decisions; architecture, data models, API contracts with rationale linked back to specific requirements. Task generation breaks the plan into executable work items ready for implementation.

Phase 3: Implementation. Tasks that can be run in parallel execute simultaneously. Automated unit and integration tests are built out that are at first expected to fail, following TDD’s philosophy. Modules are coded based on the tasks generated in the prior phases and on the fly, corrections take place based on the results of the testing modules. The code is iteratively generated and run several times all the while ensuring that it doesn’t violate the original constitution and planning documents.

Phase 4: Continuous monitoring and improvement. The feedback loop doesn’t end at deployment. Production metrics, incidents, and operational learnings flow back into the specifications. A performance bottleneck becomes a new non-functional requirement. A security vulnerability becomes a constraint that shapes all future generations. User feedback triggers spec revisions rather than ad-hoc patches. When requirements change, and they will, you update the spec and regenerate affected components systematically, rather than hacking fixes into code that slowly drifts from its original intent.

Everything lives in version control. Feature specs get their own branches. Changes are tracked, reviewed, and merged like code. Your project’s intent becomes a first-class citizen with a full audit trail.

What This Won’t Do

A few honest caveats. SDD won’t eliminate the need for skilled developers. Specs still require human judgment: understanding user needs, making trade-offs, ‘gut feel’ and knowing what to build in the first place. The mechanical translation gets automated; the creative work remains human.

It won’t work with vague inputs. “Build me something cool” produces garbage. The methodology rewards precision. If you can’t articulate what you want clearly, no amount of tooling will save you.

It won’t rescue bad architecture. If your foundational decisions are wrong, or you’re just keeping your existing workflows and throwing SDD in, you’ll just regenerate the same mess faster. SDD amplifies competence; it doesn’t create it.

The Shift Underway

Here’s what I keep thinking about: what changes when we stop treating code as the primary artifact?

There’s genuine craft in well-written software, and part of me wonders what happens to developers when code becomes regenerable output and basically a commodity artefact that is no longer the defining fulcrum of quality. But there’s also craft in system design, in translating fuzzy human needs into precise specifications, in knowing which trade-offs matter. That work doesn’t disappear. It moves up a level of abstraction.

We’ve spent decades building sophisticated tools for manipulating code. But now I find it hard to foresee a future where typing in millions of lines of codes is the most efficient use of an engineer’s time. We’re not talking about if this happens, but only how much time it takes before the industry adapts to this new approach.

So now we need equivalent sophistication for tools that aid in manipulating intent and clarifying thought. The developers who thrive in this world won’t necessarily be the ones who write the most elegant implementations, they’ll be the ones who can think precisely about what systems should do and why.

And the code will flow from that.

Patrick Chugh is a Technology Consultant specialising in financial enterprise systems and has held senior leadership roles at HSBC, AWS, and Credit Suisse. As a Solution Architect, he has advised C-level and senior leadership at JP Morgan, Santander, and Barclays. He’s the creator of Terravision, an open-source tool for generating architecture diagrams from Terraform code.